Ludum Dare #25 Post-mortem

👋 This page was last updated ~13 years ago. Just so you know.

Last week-end, I participated to Ludum Dare for the fourth time in a row!

Downloads: Linux (64) | OS/X | Windows

Story

So here is our entry: Legithief. The backstory is simple, yet cunning: you are an ordinary thief practicing ordinary acts of thievery in the houses of ordinary people to make a living. But one day.. you are quietly robbing yet another home, when you are suddenly smashed in the head with a bat.

You wake up in a basement, face to face with a dragon. He goes on to ask you who you work for, and when he understands that you are just a piss poor thief of no fame, laughs abundantly. Then you go on to learn that he is working in insurance, where, according to him, the real money is. Faced between the choice of either getting your ass burned by the dragon or helping him get more insurance contracts from innocent people, you get on your way to frightening the weak and rampaging their stuff for a few more bucks.

About Ludum Dare

Ludum Dare is a competitive game jam. It has two variants: the Compo lasts 48h, and you should do it alone, with no external help whatsoever, without re-using any pre-made asset (using game engines is allowed, though, but not stock images for example).

Since I do not really like to make games alone, I have partaken instead in the Jam: it spans over 72h, you can work in a team and re-use stuff you have done before. However, I did not re-use a lot, except for code.

I jammed with my usual buddies, Sylvain and Einat, with whom I had made a few other games earlier, including Lonely Planet.

Doing a proper post-mortem

In the previous editions, I never really did proper post-mortems, and that’s a shame. I’m a big proponent of self-healing, especially via cathartic writing (which I did heavily, in private, for the past few years).

For those who’ve never done it, Ludum Dare is a fantastic experience. For 72h you get to focus on nothing but your game (provided you’ve accomodated for 3 days of free time, which can be hard for some). This helps you reach levels of productivity otherwise reserved to the Ballmer peak.

However, there is some severe post-trauma. Especially if, like me, you completely disregard your body’s need for sleep during most of those seventy-two hours. Also, your game always looks better while you’re coding it than after it’s all done. And some of the negative feedback you get in the comments - while always polite, and most often to the point - can fuck you up.

For that reason, it is a good idea to write down exactly what went right, what went wrong, and how you can do better next time. I’ll try not to forget anything, and settle in, this could be a long one. Also, I’ll try to dabble on the technical side of things, just so I can show you guys some code, because I just set up my blog with syntax highlighting and I’ll be damned if I don’t use it.

Timelapses

A tradition in Ludum Dare events is to use software to take regular screen captures of your work session. This year, both Sylvain and I did it. Here are our respective timelapses (I suggest you watch them both at the same time).

This is Sylvain’s timelapse: it’s mostly drawing, and is probably the most entertaining to watch. Near the end of the video, Sylvain went back home so his later work (including level design) isn’t shown, which is a shame because it would have looked awesome :)

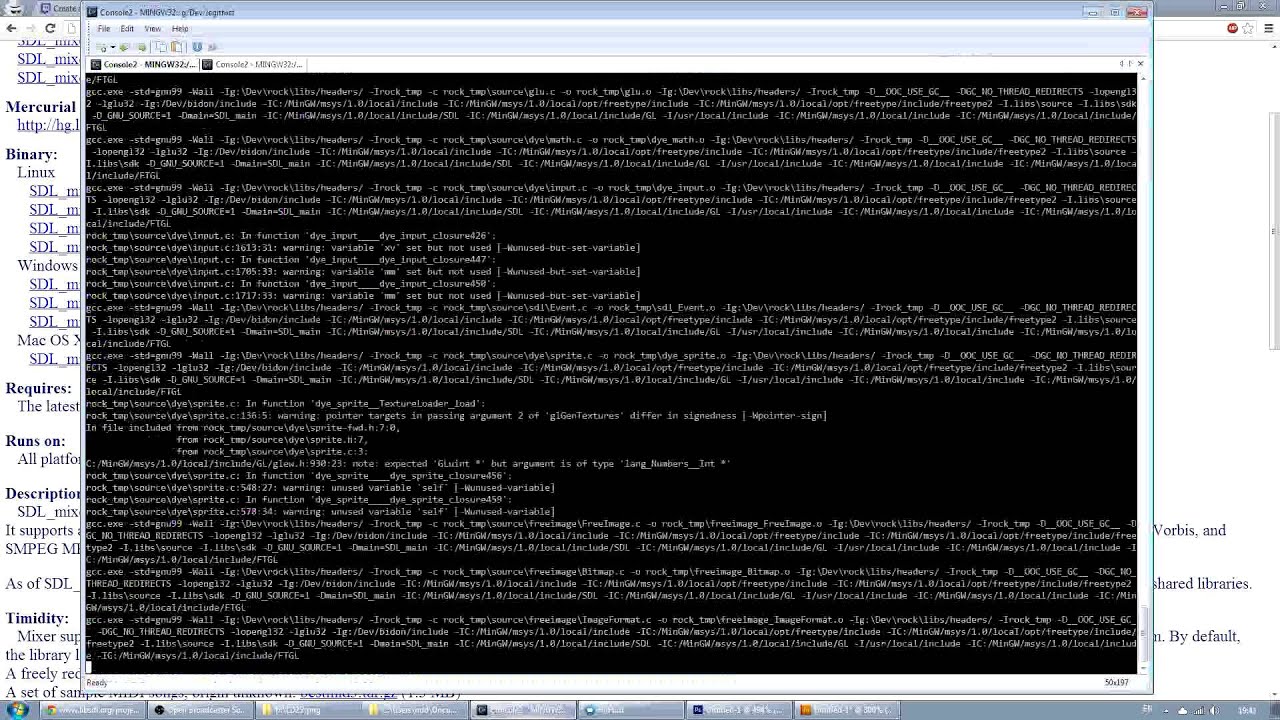

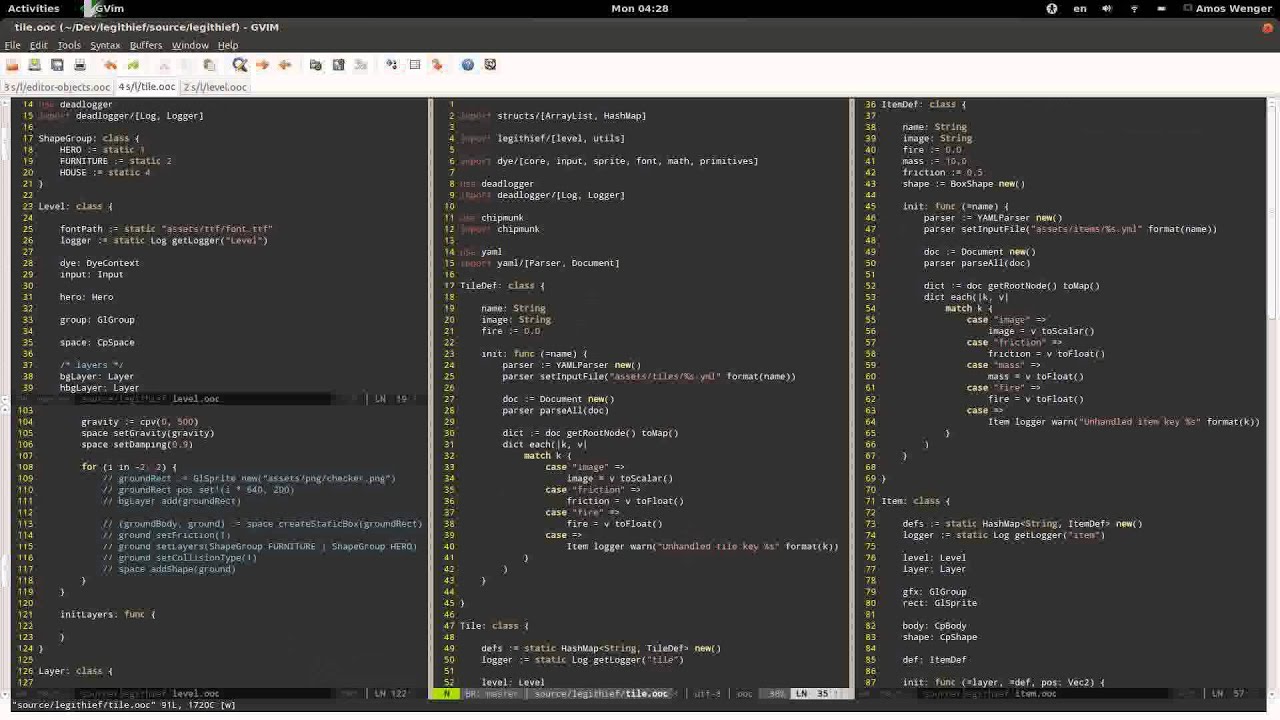

And this is my timelapse, it’s not very exciting because there’s a lot of code, but you can see that I’ve compiled and ran the game probably over a hundred times during the course of this Ludum Dare. It’s also a testament to my dedication to concentrating on boring, colored text in multiple window panes, tabs, and terminals :)

Note that I wasn’t always working on this computer: I also switched to the Windows tower (first timelapse) at times, and when I was too tired, I switched to my MacbookPro to code from the bed.

Let’s now review what went right, and what went wrong!

What went right: the language

Just like my previous Ludum Dare entries, I used the ooc language. ooc is something I started on a whim, back in 2008 when I was studying micro-engineering at EPFL. We had a project to do in C and I had gotten too used to Java, so I wanted classes! I worked for a few months on an ooc-to-C transpiler, written in Java, and in the last week, wrote the assignment in ooc. It was pretty advanced at the time, ie. it used GTK along with OpenGL (instead of the recommended GLUT.. urf).

A few years later, and ooc has syntax highlighting on GitHub, via Pygments, and if you open a .ooc file in GEdit in, say, the latest Ubuntu, you’ll have colors as well. If that’s not a life achievement, I don’t know what it is.

Anyway, the language choice did not penalize me. Since I designed the language, I did not have much to learn (obviously). But riskier was the toolchain: I know rock, the ooc to C compiler written in ooc, is not exactly exempt of bugs. But then again, neither is GCC or, god forbid, Visual C++. Anyway, I did not encounter issues I could not work around, and the good thing is that since I’ve offloaded the maintenance of rock to Alexandros, I now get to complain to him instead :)

Here are a few things I like about ooc. It forces you to write readable code: you can’t write stuff that’s too smart, yet you can get down to (almost) bare metal if you need it. It’s definitely not a “clean” language, and not safe in any way, but it’s a surprisingly good middle ground between a language like C and an interpreted language. It has a proper module system, an aerial syntax, and the code it generates compiles on Windows, Linux and OSX at least.

So for example, one way to do a game loop would be:

Game: class {

millisPerFrame := 1000 - 60

running := true

init: func {

// init level

}

run: func {

// init everything

while (running) {

prev := Time runTime()

// update game

now := Time runTime()

delta := now - prev

if (delta < millisPerFrame) {

Time sleepMilli(millisPerFrame - delta)

}

}

// cleanup

}

}

This showcases a few things in ooc: space is used to access member fields and methods instead of dot, there’s no semi-colons (you can use ’' to span multiple lines if you wish), ‘:=’ declares, infers the type, and initializes. You get basic flow control like for, while, if, and match.

Another nice thing is .use files. They allow you to use another ooc library easily, and it takes care of the dirty stuff like linking to the right C libs, including the right headers, etc.

As an example, a minimal SDL example would be:

use sdl

import sdl/Core

main: func (argc: Int, argv: CString*) {

SDL init(SDL_INIT_EVERYTHING)

screen := SDL setMode(640, 480, 0, SDL_SWSURFACE)

SDL wmSetCaption("SDL test", null)

SDL delay(2000)

SDL quit()

}

But enough about the language. There’s resources online to learn about it, and if that’s not enough, just bother me by e-mail and contribute to the Wikibook about it :)

What went right: Cross-platform

Tightly coupled with the last section, building the game to be cross-platform was a breeze. I used only portable frameworks, and I used my homebrew fork for Windows to compile most dependencies, including GLEW, SDL, SDL_mixer, Chipmunk, libyaml, etc.

I still have separate Makefiles for Linux, Win32 and OSX but only because of pesky include paths / library path issues.. they’re actually very short and sweet.

Having such a build system allowed me to quickly iterate with builds on all three platforms. Mostly, I was developing on Linux and OSX, and uploaded Windows builds of the game regularly for my teammates.

What went right: Sound

In the past year I’ve acquired high-quality equipment for audio capture, and so did my friend Sylvain. However, for this game, the only capture we made was of me doing a bit of voice acting for the initial backstory. (If you haven’t checked out the game yet, it’s worth it just for that - just so you can make fun of me for generations to come, or come play it at my wedding).

All sounds effects were sourced from Freesound a well-known (and invaluable) resource to Ludum Dare game developers. It contains eveyrything you don’t have the time or means to record during your LD jam. I gathered 2-3 samples for every sound in the game: bottle crashing, cash register, hero grunting. It was fun!

What went right: Teamwork

This is the first LD I do where I get to start from the beginning with a teammate, ie. Sylvain. Einat joined us later to add a few graphic elements to the game. It was very enjoyable to be together to brainstorm at the beginning. We had a hard time coming up with an idea at first but then it went smoothly, I could quickly integrate what Sylvain drew.

What went wrong: Frameworks & tools

Sylvain mentioned that he only learned the shortcut keys to Adobe Illustrator later during the LD. Having former training (for example during the warmup) would have avoided that.

I did a big mistake myself… for the game, I’m using ooc-yaml, a wrapper over libyaml. It was somebody else’s project that I forked and the description read: “YAML parser and generator based on libyaml”. And turns out the generator part was missing! At first, I only did a level loader and wrote levels by hand, so I didn’t see the issue.

Also I waited 48h to implement the “save” feature in the level editor. The result is that I spent 4 hours on it, because by that time I was really tired and confused libyaml return codes (1 on success, 0 on error) with error codes (0 means no error, nonzero are specific errors) and so thought my emitter didn’t work for a long time.

Something else that went wrong was the sound library I used. At first, I used a library of mine, abstracted over cubeb, a minimal, low-level sound library. The nice thing about cubeb is that it’s so light, so it wouldn’t add much weight to the final game, which I found great. But for some reason when I recorded a bit of voice and tried to play it back as an ogg file, it error’d. I had no time to debug, so I switched to SDL_mixer instead. It was quick, but still time lost. Then I learned that “loops” must be 0 if you want to play the sample once (obvious in retrospect), and other stuff like that, but at least the game ran on all OSes and all the audio files I could throw at it.

More trouble: the ooc bindings for Chipmunk, the physics engine I used, were far from complete (but this time, I only have myself to blame). Also I didn’t know how it worked. Although I had worked with physic engines before (ODEJava, JOODE, some Box2D), every engine has its quirks and must be mastered. As a result, some features were buggy, like stairs and ladders, which were the first things people noticed in the reviews, unfortunately

What else… I didn’t want to re-use ldkit, mostly because I wasn’t happy with how the bioboy codebase ended up, and because it was based on cairo and I didn’t want the dependency on Windows (possible, but painful). I wanted to go SDL+OpenGL only, so I did just that.

However, when I started, dye, my new graphics framework, had… only window creation. During LD, I managed to add texture loading, font loading with FTGL, textured squares, cropped textured squares (which we did not need in the end), animations from PNG sets, sets of animations that you can “play” at different speeds, and various primitives from segment to square to cross to grid.

On the plus side, using it is quite nice. As long as you’re not doing full-GUI stuff (another, higher-level framework would be required then), it’s quite convenient:

dye := DyeContext new(640, 480, "Dye font example")

text := GlText new("Sansation_Regular.ttf", "Dye with text o/")

text center!(dye)

text angle = 45

dye add(text)

dye render()

But I had to build it from the ground up. I did steal some of my code from ldkit, like the math code (vec2, vec3), and the input code (which I thought I remembered as being more modular…)

Similarly my new audio framework, bleep, is pretty much as simple as it gets:

bleep := Bleep new()

rain := bleep loadSample("rain.wav")

rain play(-1) // play rain in loop

bleep playMusic("jazz-piano.ogg")

But I had to do everything by hand as well.

Wait, there’s more! Before starting LD, I did a ‘game framework’ with message passing between fully dynamic objects, called doll.

I started developing the initial version with that, but then quickly realized it wasn’t going to cut it: defining ‘prototypes’ from within an ill-conceived DSL, listening for every possible type of message was going to be too long. And to have the full benefits of doll, I should have wrapped every other library I was using in the same style.

Lesson learned: I should have prepared all those frameworks before. And also, I should stop changing my mind about what technology I want to use!

What went wrong: Scope, time management and level design

One of the usual sins of LD participants is to plan for too big… the game as we originally envisioned it was supposed to be an infiltration / snaeky / stealth game: you would have to quietly break into people’s house, and sabotage them and only later “make them notice” (by making noise for example) so that their fear level would increase.

One of the core mechanics would have been to balance between fear and health. For example, if you just throw a molotov in someone’s living room and burn them to death, you won’t gain insurance money because they’ll be dead. Of course, their family might take life insurance for the other members of the family, etc. See the scope creep already?

Without even worrying about noise, fear management and behavioural AI, navigational AI was going to be a challenge as well - and 60 hours in, I still did not have time to tackle it! The fact that I had to spend so much time developing frameworks also played…

…but also, I made a level editor! Typically the thing you usually don’t have time to do during the Jam, and definitely not during the Compo. Well, I did one, and a pretty sophisticated one as well. Grid snapping, multi selection, multi layer editing loading/saving from/to YAML, object outlines… there was everything!

In a way, the level editor was a success because Sylvain was able to use all the graphics he hade made during the LD to design some levels in the last hour. If it wasn’t the case, we wouoldn’t have had any levels at all :D The same thing happened with the code: in the last few hours, I realized we’d never get what we originally thought of done, so it was time to fall back to plan B… destroy everything! I added the “objects get black when destroyed” feature literally minutes before the deadline.

But it took way too much time to develop the level editor on top of all the frameworks… the result? We’re not even using all the features of the game. For example, I forgot to mention that the mouse is used to control the camera in the game. So we got some bug reports of people thinking the character is supposed to turn around simply when you move with the keyboard keys, whereas the mouse controls where you look, allows you to see farther in the game, and also to aim where you throw molotovs - just like in a real game.

Of course, in a game where you just bash everything it doesn’t make sense. But in a stealth game it makes sense to have these FPS-like controls, because you want to see what’s happening around you. Another thing we didn’t use enough is the wooden tile I implemented: it’s present in the first intro level, and can be burned down with a molotov (which allows you to smash the dragon, by the way), but not in any of the other levels because I didn’t successfully communicate what burned in the game and what didn’t!

Conclusion

It’s always a bit disheartening to fall short of your goals and get negative feedback on something you’ve worked so hard for. But I’m happy with the codebase, and Sylvain & Einat seem to agree to continue to work on it, so we plan to release a complete version, to make sure our engine is rock-solid for the bioboy remake!

We’re starting to work together very well as team. The mood improved, and there’s fewer point of frictions in the decision process. As far as we can tell, we’re all thrilled to be working again on putting something out there, no matter what life throws at us :)

Did you know I also make videos? Check them out on PeerTube and also YouTube!

Here's another article just for you:

Making our own spectrogram

A couple months ago I made a loudness meter and went way too in-depth into how humans have measured loudness over time.

Today we’re looking at a spectrogram visualization I made, which is a lot more entertaining!

We’re going to talk about how to extract frequencies from sound waves, but also how my spectrogram app is assembled from different Rust crates, how it handles audio and graphics threads, how it draws the spectrogram etc.